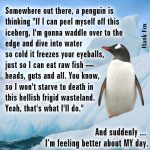

A phrase popped into my head yesterday while I was thinking about something completely different, and I’d like to toss it at you: “challenge food.”

A phrase popped into my head yesterday while I was thinking about something completely different, and I’d like to toss it at you: “challenge food.”

A challenge food is that stuff you’re expected to eat, not because it’s good, not because it’s something you would normally like, but to prove to your friends that you’re tough. Or daring. Or … willing to go along with the joke.

How many times have you heard people rave about chili hot enough to bring tears to your eyes? Or read some story about the search for the hottest-ever chili pepper?

There are other challenge foods. Raw oysters come to mind. Mountain oysters (bull calf testicles). Sheep’s eyeballs.

Considering where I came from, sushi was a challenge food for me. At least until I took my first bite, and discovered it was heavenly!

There are also plenty of challenge drinks. Everclear. Metaxa. Hell, even beer, if you’ve never had it before.

I bring all this up because challenge foods illustrate a line in human thinking, the line between “I should like this” and “This should be good.”

Or, more fully, the difference between

I should like this because everybody says it’s good.

… and …

If I’m going to like this, it has to be good.

Do you see the difference? The first one is a follow-along belief that says one’s judgment about what’s good should be based on what other people say is good. The second follows one’s own internal compass, saying that if something’s good TO YOU, you’ll like it, and not otherwise. In other words, the food is going to have to live up to you (your judgment), and not you live up to the food (in other people’s judgment).

I fell for the chili challenge oh-so-many times when I was growing up in Texas. Friends would make the burning hot stuff and gather to rave about how hot it was. “WOO!! That stuff just about burns the hair outta yuh nose, don’t it! Sweet Jesus, somebody git me a fahr hose! I think my eyeballs is meltin’! That chili’ll git the wax runnin’ outer yer ears!”

Until the day I said to myself “Dammit, I don’t want to FIGHT with my food. It’s either gonna be something I like, or I’m not going to eat the goddam stuff.” Ever since, I’ve enjoyed my own very-mildly-spiced recipe for chili, and none other.

I was surprised the first time I tasted champagne. I’d seen it in all the movies, you see, and people were sipping it and laughing, obviously enjoying it. I expected it to be sweet and light and fizzy. Instead it was this … bitter pisswater. I didn’t exactly spit it out, but I took two small sips – the second to be sure I’d been right about the first – and then put the glass down.

In fact, compared to my high school and cowboy buddies, I was very late in taking up drinking at all. I was 22 before I drank down an entire beer, or finished an entire mixed drink on my own. Beer simply didn’t taste very good to me. And even after I started drinking seriously (!) with my cowboy buddies in California, I divided mixed drinks into my own two private categories: Candy and Hair Tonic. Candy drinks – Tom Collins, Rum and Coke, etc. – I would drink. Hair tonic drinks – Martinis, etc. – I would not.

(Bear in mind this is all based on my much-younger sense of taste. Champagne no longer tastes like bitter pisswater, but it also doesn’t taste very GOOD. And still today, a six-pack of beer, which I do buy occasionally, will last me several months.)

Not to say that I wouldn’t try some of that stuff when I was out with the mule packers and had already had a few. I know what Metaxa tastes like, for instance (it probably rises into a third category – Paint Stripper, perhaps, or Human Rights Violation), but I would never, ever order it on my own.

Let’s look at those two mindsets again, though:

“I should like this” is hauled up from the deep, deep well of tribal solidarity:

This is justice because my neighbors say it is. This is right because the Pope says it’s right. This is a justified war because my countrymen say it is. This is good because everybody else seems to think it’s good. This is okay because it’s always been this way. This is the best way to do it because this is how my people do it. I should think this, and agree to this, and go along with this, because that’s what I’m supposed to do. This is real and true because the Bible says it is.

“This should be good” springs from the fountain of individual judgment:

Waitasec, is that right? Hmm, I don’t like this; is there something wrong with ME, or is it something wrong with THEM? Hell, I’m not going along with that. Jeez, I wonder why everybody thinks that’s okay? This tastes awful; I’m not eating/drinking/smoking it. I don’t like the way this is going; I’m outta here. No way am I going to put up with this. Well, shoot, that’s just silly; I didn’t sign on for this. Why is everybody standing around — can’t they see those people need help? Or even: What the fuck is up with you idiots? Can’t you see this is wrong?

I’m not knocking tribal solidarity, but there are limits. I’m pretty sure completely giving up your Self, vanishing totally into the herd, is just wrong. If you’re exactly like everybody else, you don’t really exist. I mean, you might still be walking around and breathing and stuff, but there’s no YOU in you. You become a nebbish, a puppet, a faceless, selfless nothing, pushed here and there by the tides of public opinion, or the will of corporate advertisers, or the driving whip of political manipulation.

If you default on the necessity of being an individual, you vanish in some way. You become a … thing.

But where do you draw the line between the two? On the one hand, there’s the risk you might become a non-entity. On the other, you face the danger of turning into something of an egotistical monster.

It’s not possible for me to really advise you on the thing, but several things come to mind in thinking about it:

First, the unspoken foundation of freethought is a willingness to take on the responsibility of making these kinds of choices. Once you become aware that there IS a choice, you’ll figure out where to draw your own line.

Which means, given the fact that this is the real world, and we’re only human, in the thousand SMALL decisions of daily living, a lot of it will involve the familiar “Go along to get along.” It’s just too tiring to do any different. As long as you realize there’s a small price you pay each time you go against your own values, and you judge either that the price is too small to bother with, or that the benefits outweigh the cost, you’re set.

Second, in the BIG decisions of your life — the health and welfare, life and death of you and your dependent loved ones – it has to be you making the decision. Every time.

Third, if the choice involves another person – a friend or relative, for instance – be sure it’s your decision to make. If it’s them paying the price of the choice, I would suggest it’s not your place to make that choice.

Finally, there is one decision-making arena where you can ALWAYS reliably default to your own personal judgment: Anytime you’re expected to follow along completely, to obey without questioning, that’s the time you must not follow along. The time when you have to back out, call a halt, and take the time to exercise your own ability to investigate, evaluate, and judge.

Whether it’s pressure from peers, the danger of official sanctions, or just a context of unspoken expectations, if the situation suddenly turns your life into a cattle chute, you must — at least in your head — refuse to be a cow.

A good thing to remember the next time you’re asked to go along with a war. Or with a church.

_______________

By the way, do click on the photo to embiggen it. It’s one of mine, and of someone I know. The bridge is about 65 feet high, the young man is 19, and … dayyum. (Yes, he survived.)

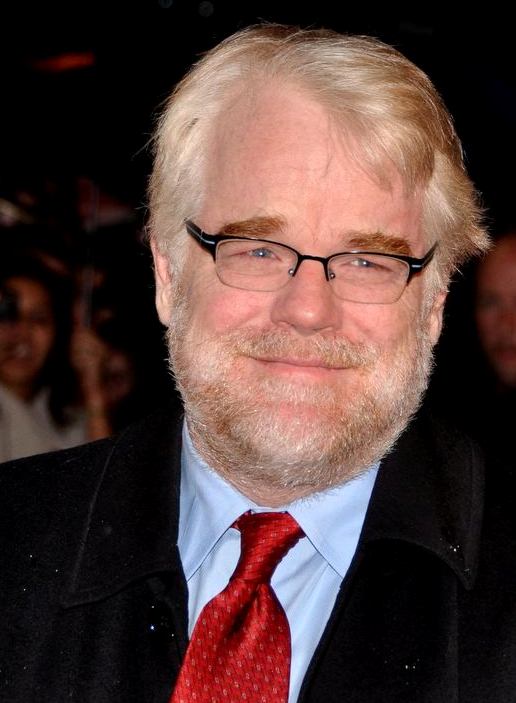

Apparently actor Philip Seymour Hoffman died. He ROCKED “Capote,” but hell, I liked him as far back as “Boogie Nights.”

Apparently actor Philip Seymour Hoffman died. He ROCKED “Capote,” but hell, I liked him as far back as “Boogie Nights.”