As an atheist, you hear it all the time – the in-your-face assertion that Humans are “wired for God.” We believe in gods, we’re told, because it’s natural to us. Because we have something in us that NEEDS a god or gods. Maybe because it carries some evolutionary advantage, so we evolved to have it.

As an atheist, you hear it all the time – the in-your-face assertion that Humans are “wired for God.” We believe in gods, we’re told, because it’s natural to us. Because we have something in us that NEEDS a god or gods. Maybe because it carries some evolutionary advantage, so we evolved to have it.

The conclusion, in the mind of any faith-professing Christian, is that we’re this way because there really is a god, or at least some sort of “something bigger out there somewhere” that makes it so. We believe because we need to, because we have to, because to do anything else makes us less viable organisms. Lacking a god-need is an evolutionary dead end.

In how many conversations have I had someone tell me “Well, I don’t necessarily believe in God, but I think there’s something out there. Something beyond anything we know.”? I’ve heard that a LOT. Even people I would otherwise consider full atheists have said such things to me.

I’ve felt that pull myself. I’ve thought many times, “We live our lives on a human stage. Everything we do is for other people. But is that enough? Isn’t there anything … more?”

I actually think there is. But it’s not God or gods or mystical superbeings of any sort. It’s this whole other thing, something real. But it’s something so much a part of us we fail to notice it.

I’ll tell you what I think it might be.

First, here’s me: Atheist. Beyond atheist, in fact. I independently came up with the term “antitheist” to describe myself 20 years or more ago, long before it was in vogue. Rather than the current fashionable pronunciation, “an-tee-THEE-ist,” I pronounced it “an-TITH-ee-ist.” I described it humorously as “Not only do I not believe in gods, but I don’t think you should either.”

But I’m also a realist. You have to face the real world and take what it gives you, even if you don’t like it, even if it flies in the face of things you think you know. So whenever I’m presented with a woo-woo idea, something I know isn’t right as presented, but which nevertheless seems to have some sort of substance to it, rather than dismiss it with “No, despite what it looks like, there’s nothing there,” I have to 1) accept whatever realness it presents, and then 2) see if I can figure out a real-world explanation for it that makes sense.

So do we have a need for gods? Are we wired for that? If not, what is it we DO have? Let’s explore a couple of conceptual trails and see where they lead.

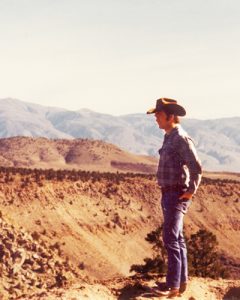

Most of us, when we talk about going hiking in the woods, or camping in the wilderness, talk about it in terms of “going out there.” We live in cities, and we “go out” when we head away from the city into the wilds.

But it’s the other way around, isn’t it? Because cities are NOT our natural environment. Our natural environment is … the natural environment. It’s where we grew up, where we evolved to be. We’re not going OUT when we go to the wilds, we’re going BACK. The only time we go OUT is when we trek from the wilds into a city.

Our home, our real home, is in the woods, on the mountains, in the midst of trees and creeks and blowing wind. It is out in the sun and rain, in the dirt and dust, the pollen and bugs and mud. It’s out where we can stomp around in our bare feet, filling our toes with mud, seeing wild animals and birds and distant valleys, blue sky and fluffy clouds, nights filled with full moons and stars. Where we can taste berries and ripe fruit, where we can smell waterfalls and flowers and our own sweat, but also skunks and even blood and death.

I know you’re thinking all this is some kind of artsy-fartsy poetic allusion, but I’m dead serious. CITIES ARE NOT OUR NATURAL ENVIRONMENT. Cities are alien. Artificial.

They’re not even all that good for us. Yeah, we’re comfortable in our engineered and sanitized ’burbs, but we’ll also eat until we weigh 300 pounds, and then whine that we feel sick all the time. We’ll tolerate noise and pollution and chemically-adulterated foods until it weakens and kills us.

Think about all the animals we’ve invited out of the wilds, bringing them into towns and cities to live with us. Compared to their wild cousins, domestic animals are almost invariably weaker and dumber. More fragile.

Wild animals are generally tougher, stronger, faster and fiercer than our pets and livestock. We’re used to how soft and cuddly kittens and puppies are, but pick up a baby raccoon – which I did, years back – and you’ll be shocked at how hard it is. The little bastards are tough as boiled leather.

Just as our pets are, we humans here in cities are soft. Less robust. And probably a lot dumber than whatever wild cousins we once had.

But there’s a deeper point than that our real home is in the wilds. It’s this: That we’re a part of the world around us – profoundly inseparable from it. We’re no more alive without the world around us than a toe is alive when removed from its foot.

Allow me to argue the point:

Say we wanted to define “human.” We’d probably have a fairly involved description, possibly accompanied by a picture of some individual person, maybe some other animals for comparison. But what we wouldn’t have is a full understanding of what being a human means. Because we never really even think about it.

You’re sitting there right now believing yourself to be a complete individual, a discrete quantity of personness, probably picturing your exterior, your skin, as the boundary between “you” and “everything else.”

But your skin is NOT the boundary. In fact, when you really think about it … well, think about this:

Take a human. Hang a large sign around his neck, “Human.” Have him stand on a stage with no other person around, and take a picture of him. QED, this is a human, right? This is all a human is, all there needs to be. No, because you still haven’t separated him out from a great deal of other stuff.

But take that same human and drop him through a portal that deposited him someplace where he could REALLY be alone – say 50,000 lights years away, out in the space between galaxies. What do you have? A dead person.

We never think about it, but the definition of “human” has this hidden implication – that the human is alive, and that quite a lot goes into that aliveness. We never think about the food and water, the gravity and atmosphere, a solid place to stand, other people around to make life work, other animals and plants, a lot of them, somewhere nearby to eat.

The atmosphere we breathe doesn’t just go in and out of our lungs, it seeps into and out of our skin, penetrating us on a cellular level, maintaining a pressure without which we’d die in seconds. The food and water we consume, and later excrete, forms a flowing river of input and outgo, without which we’d also die in short order. And the thing is, the food and water comes from somewhere, the air comes from somewhere.

So we are linked, bound into, an entire system of processes that extends backward in time and outward in complexity in a way that no end can really be found. The oceans? Part of us. The mountains? Part of us. The rainforest, the arctic, the deserts? Part of us. The clouds, the rain, the snow, the bees, the plants, the rocks, the crustal plates, all part of us.

The sun? Oh, yeah, part of us. BIG part of us.

And WE are part of IT. We don’t just live on Earth, we’re nailed into it, soaking in it, connected to it in a way that allows no separation. Even the International Space Station astronauts can live for only a brief time before they start suffering serious health effects – and they get continuous supplies from Earth.

There is only one way to define “human” without also including all this other stuff – the way that specifies “dead human body.” To have a live human, you have to include everything else … at least as far out as the sun.

We say “we” and we say “I” but those are rhetorical conveniences that have no true reality. The view of ourselves as separate and individual is purely subjective – a view which is fantastically, stunningly, titanically oversimplified from the real situation.

The truth is, our mysterious and powerful “something out there” is the natural world. Yet here we are off in cities, acting in our vast ignorance as if we’re discrete individuals, separate from our larger inclusionary selves.

On some level, I think we know this. We yearn for that larger part of us. We reach for it. We desire to be a part of it, to touch and be touched by it.

But divided from the natural world in cities, ignorant of it, we think the missing “something out there, something larger” is a god, or gods, or some other mystical formulation.

It’s a drastically wrong, tragically misleading answer. But sadly, it’s all most of us can understand or accept.

In pursuit of my Beta Culture concept, I’ve been thinking a lot about Culture over the past couple of years, and I’ve recently been making some interesting connections. I like to think I’m getting close to understanding the meat of it. Here’s a recent thought:

In pursuit of my Beta Culture concept, I’ve been thinking a lot about Culture over the past couple of years, and I’ve recently been making some interesting connections. I like to think I’m getting close to understanding the meat of it. Here’s a recent thought: