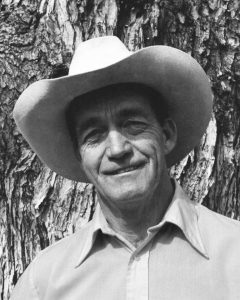

Daniel Franklin Farris, b. March 22, 1934, d. Nov. 6, 2011

Daniel Franklin Farris, b. March 22, 1934, d. Nov. 6, 2011

I’m writing a piece for American Atheist with the working title “The Idea of Souls,” in which I look into some of the civilization-wide cost of believing in ensoulment. The writing of it coincides with the 5-years-ago-today death of my surrogate Dad. What follows is a feelings-level reaction to dealing with that anniversary.

This is an atheist — me — grappling with the death of a loved one. Nothing in atheism says we don’t feel all the same feelings goddy people feel — the same sorrows, the same yearning for it not to be. The difference is, we don’t fall into permanent fantasies of eternity and immortality, into imagining that every life is cosmically significant and that someday, someday, we’ll all be together again in glorious paradise. We accept the fact of death — real death — and simply live with it.

Someday I’ll write a book about it.

____________________

People die. And I hate that more than anything.

I’ve thought a lot about … not just the deaths of loved ones, but death itself. How it takes from us the bright lights of civilization, and replaces them with darkness. With nothing. So that we have to struggle to create new lights and put them out there.

I was never a great fan of Lucille Ball. There was something about her comedy that bothered me. The heart of what she did was often about personal embarrassment. She would do something silly that turned into a disaster, and the funny part was how mortifying it was. It just wasn’t my type of humor. But other people liked her, eventually enough that she was one of those legendary superstars, known to everybody.

Bob Hope was the same type of star. Timeless, immortal, forever.

And yet …

If you asked young people today about Bob Hope or Lucille Ball, they would say “Who?” Or maybe “Oh wait, wasn’t she on a TV show or something? And he was like this guy who’d go over and put on shows for the troops? I think my parents knew about them.”

One of the funny things about getting older is there’s all this stuff that happened in your life, events and people you consider Memory, but that younger people consider History. To them it’s a lot of dry, dull stuff that happened way in the past. Genghis Khan, John Glenn, it’s all the same. Eventually, it’s all the same.

I like to think there could be people who were so accomplished, or so good, they’d be nailed into the fabric of reality forever. I’m talking about something more than mere History, where names and dates and victories are recorded in books. I mean they’d be embedded in the bedrock of the Universe, so that everyone and everything that came after would be aware of them. You and I could look up at the sky and just KNOW things. “Vorpal Grishnak? Oh, yeah, he’s the guy who lost his life saving billions of Randalians from that plague on Zarefia IV, in the Korbin Sector.”

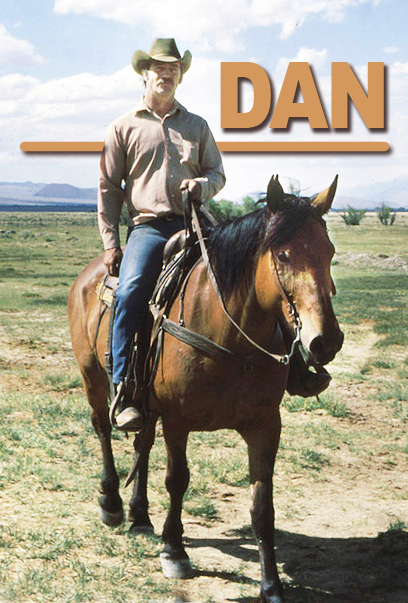

And “people” out there could look up at their sky and say “Oh, yeah, Dan Farris. Hank’s Dad. He’s the Earth-human who devoted 60 years of his life to mule packing, taking people into the Eastern Sierra mountains to camp and fish. Helluva story teller and all-around good man.”

To my sorrow, there’s nothing like that. Hell, we can’t even manage History, most of the time. I see cemeteries all over Upstate New York that have pre-Revolutionary tombstones in them. Some of them are so old, hundreds of years, that the chiseled inscriptions have been worn away by rain. I asked at an old church one time, “Are there permanent records somewhere that tell who these people were?” The guy chuckled and said “Paper records get burned in fires, eaten by rats, damaged by water. The stones ARE the permanent records.”

Who would ever imagine a carved granite stone would ever wear away to nothing? And yet they do. The names fall away into darkness, following the people who sported them by only a few years.

I saw a picture at a museum in South Lake Tahoe a ways back, a dozen or so loggers standing on and by a huge felled tree. A dog had wandered into the frame, and a team of mules stood in harness nearby. I realized that every one of those men had lived lives as long and as memorable as mine, or anybody’s, and yet today not only are they gone, but everybody who ever knew them, or even heard stories about them, is gone. The entirety of the impression they had left on the world was this one picture, a shadow-play of silver crystals catching one brief moment in their lives, showing their faces but telling nothing of their story.

And here’s Dan, who meant the world to me, falling away into that same darkness.

He had his day in the sun. He took life into his hands and shaped his own course. He had his victories and his disappointments. He was treated both well and shabbily by the people around him. He found love, and gave love, lost love, and gave still more. He packed mules, he wrote, he told stories. Breaking bones, skinning his knuckles, dessicated by the dry air and the high country sun, he unfailingly stood tall, stood strong, stood steadfast, making a rare impression on the people who knew him. By no means did he come away from life with everybody loving him, or even respecting him. But he lived on his own terms, rock solid, and I see that as victory of a sort many of us never manage.

I have thought many times that we humans have this two-part gift, that we get to be Human and Beast both. We have our Humany parts – which are language and humor, intelligence and creativity, in the heart of our cities and civilization. And we have our Beastly parts – which are things like eating and sleeping, fighting and carousing with our packmates, at our best delving into the wilds around us, becoming one with it.

It seems to me that to be the best person, a COMPLETE Homo sapiens, you have to be not just a good Human, but also a good Beast. And Dan was a good human, intelligent and funny and creative. But he was also a very good Beast – not just good at living in the wilds, but feisty and lusty as well, in every part of his life. Glorying in his beastliness, he ended with memorable scars and stories, but he lived up to the best of both roles.

He’s one of those people who should be branded on the hide of Earth, recorded and preserved forever for all who come after. There should be a story, a vivid memory of him, floating in the clear air and the crystal waters of the Eastern Sierra, so that anyone who came after, the moment they took their first deep breath of the backcountry air or drank the cold, delicious waters of a Sierra stream, would instantly know him. They’d look up in surprise, the water still dripping from their lips, and go “Oh! Dan Farris!” as the memories unfolded in their heads.

But … we have nothing like that. Bob Hope and Lucille Ball, Genghis Khan and John Glenn. And Daniel Franklin Farris. They fall away into darkness, and nothing but words on paper, carvings on stones, hold them here.

We live our lives, creating our own memories and impressions, but also loving and cherishing the memory of each other to the best of our ability. What immortality there is, we provide it, for as long as we ourselves live and retain the memories.

Some of us get stones, some of us get stories in history, some of us even get statues. But some get only memories in the minds and hearts of the people around them.

To a writer, one used to putting down thoughts and words on paper, those memories are as vivid as any bronze statue, recorded for me in a timeless Now. I see Dan as he lives his life on the sunlit trails of the Sierra. The creak of his saddle sounds in the crisp air of a mountain pass, the clink and thud of horse and mule shoes ring and thump on the dusty trails. I see his strong hands on rope and tarp and pack box. I hear his friendly voice as he tells stories by firelight, hear his laughter at the punchline of a joke. I see the last dying light of a Coleman lantern strung overhead, and hear its final little pop.

In the darkness, five years past, I feel him give my hand a last squeeze, see him smile briefly from a hospital bed, a smile that lights the infinite night for me, a light that will – no matter who else remembers or cares – carry on with me for all the years of my life.

For me, it will never be “Here Lies Dan Farris — little-known man of this one small place.” It will be “Here STANDS Dan Farris, A Good Man, A Mule Packer and Mountain Guide, A Rare Specimen Of The People Of Planet Earth, Unforgettable And Unmatchable In All The Worlds.”

The world is poorer for his loss, and there will never come another like him.

But maybe … for this life, for this history, for me, the one was all I needed.

.

Ha — of course that doesn’t stop me from thinking, pretty much every day, “Dammit, Old Man. I miss you.”